- The Human Stream

- Posts

- The Games We Play

The Games We Play

An Article on Game Theory, Trust, Safety, and Health System Improvement

Guide map for Readers

(Estimated reading time: 15–18 minutes)

This article is a comprehensive exploration of Game Theory as a lens to frame the strategic interdependencies of modern healthcare. Before diving in, here is how you might navigate this piece:

The Lens: We move beyond a retrospective of the pandemic to examine the hidden rules governing today's most critical challenges: the complex balance between patient safety, operational capacity, and staff wellbeing.

The Immersion: Several interactive games and simulations are embedded throughout. To fully experience these "digital labs," you may require 15–30 minutes of additional time.

The Payoff: The article concludes with practical implications and proactive measures for healthcare leaders to preserve trust and cooperation in high-stakes environments.

Two Worlds on One Board

Watching the final season of Stranger Things brought back a flood of memories from a particularly fond time in my early childhood - the three years I spent in Gainesville, Florida, in the late 1980s. The epic final events of Season 5 happen to be set in roughly that same period.

In the humid Indian summer of 1985, my dad, to pursue his PhD at the University of Florida (Go Gators!), transplanted all of us from the familiar, sedate rhythms of Chennai (then Madras) to what seemed to my eight-year-old self a completely otherworldly and magical place. We arrived at Atlanta Airport to the strains of Shattered Dreams by Johnny Hates Jazz. For me, it was the soundtrack to one of the best times in my life.

Back then, Gainesville was the quintessential sleepy university town “where nothing happens”, a lot like the fictional Hawkins, Indiana. Stranger Things accurately captures so much of the vibe of that period: from its carefully curated soundtrack, the VHS cassette tapes, the ridiculously oversized walkie talkies, the obsession with Dungeons and Dragons, Commodore 64 and Atari systems, trucker hats, and cruiser bicycles. Most of all it reminded me of that sense of wondrous adventure we experienced everyday as children, from searching for arrowheads around Lake Alice (while giving the alligators a wide berth) or constructing ill-informed and ridiculously dangerous booby traps to keep ‘undesirables’ (basically all girls) out of our hideouts.

Alligator on the shore of Lake Alice within the University of Florida campus in Gainesville, Florida (also in picture are two softshell turtles) - used under creative commons licence 4.0 - retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Inexplicably, Stranger Things even nails the exact ‘colour tone’ of my vivid memories of that special time.

Without giving too much away, the final cataclysmic act involves a “Hail Mary” of sorts, where this band of teenage friends attempt to save the world with a few everyday resources (ok, and some serious firepower - it is the U. S. of A after all). However, the main source of their success is unbounded creativity and courage in the spirit of every 80s boy’s hero - Angus MacGyver.

That TV Show was a favourite of mine. MacGyver, a genius secret agent with the Phoenix Foundation, would foil many a devious plot using nothing more than his intellect, improvised gadgets and everyday items. Aside from the sheer entertainment value, the show also conveyed a deeper (and still critically relevant) theme that many problems can be solved without resorting to violence.

© 2008 TNS Sofres, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

I had forgotten all about MacGyver until he resurfaced once more in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. But this time MacGyver was a verb -"MacGyvering”. It was now being used (at least locally) to describe a myriad of efforts by various global clinical teams as they prepared for the impending crisis. Its use grew even more as stressed health systems furiously navigated the many complex operational and safety challenges the pandemic threw up in the months that followed. However, the connotations weren’t always positive.

Around that time, I was setting up the Bridge Labs program within my organisation, a pandemic-era innovation initiative aimed finding new ways to rapidly scale frontline innovation capacity (more on that here and here) - exactly the kind of frugal innovation that was already happening in pockets at the early stages of the crisis the world over. Leading this effort gave me a unique opportunity to observe how various parts of our system thought about and responded to arising challenges, from the highest levels of leadership to the many somewhat autonomous frontline teams spread across various health services.

The patterns that I witnessed while novel to us, were also being simultaneously described in the United Kingdom and in various North American health systems - effectively anywhere that large high-reliability healthcare oriented organisations needed to learn to bend and flex in ways they had never done before. They had to respond to a complex ‘adaptive’ crisis when their architecture, systems and organisational hierarchies had been painstakingly evolved to produce a very specific set of outcomes in predictable ways.

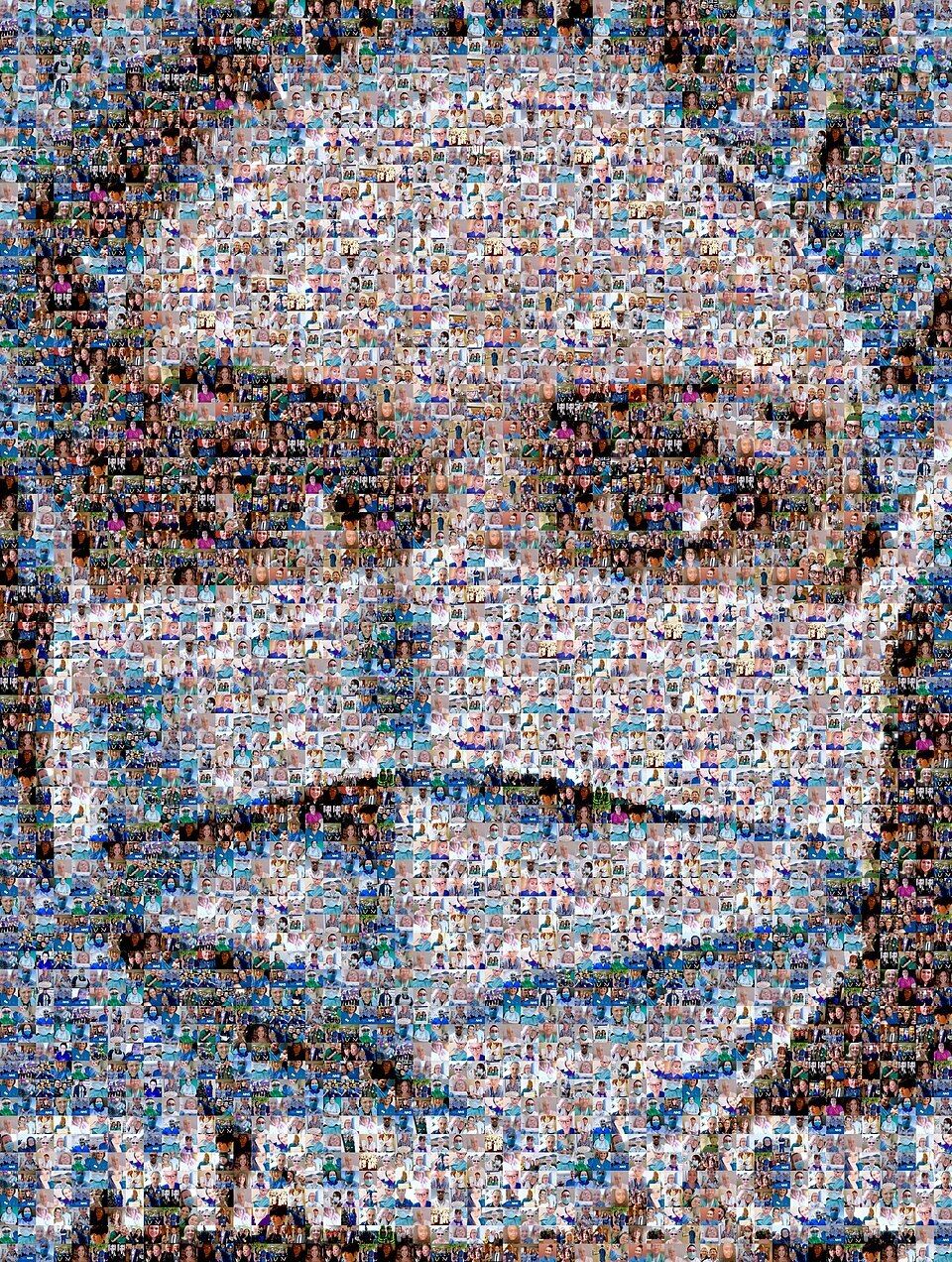

Nathan Wyburn, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Quite an impressive body of research literature has since accumulated (some of it in real-time) on the system-level shifts and the many innovations that came out of the pressures of the pandemic.Several theoretical papers have looked to explain what we observed on the ground, through complex systems theory, behavioural economics, and socio-anthropological lenses.

In this piece however, I want to focus on a small subset of that literature, which applied the field of Game Theory to the crisis.. I do this to illustrate how game-theoretic concepts are incredibly relevant when thinking about how semi-autonomous systems like healthcare respond to all sorts of things not just pandemics. Even the safety, performance, workforce, and bed capacity questions we are still grappling with today.

We will get back to how game theory explains much about the pandemic, what all that “MacGyvering” was about, and perhaps even some crossover motifs with the deeper premise of Stranger Things. But first, lets build some basic familiarity with what Game Theory is.

A quick Primer on Game Theory

At its heart, Game Theory is not about board games or casinos, even if that is the context where many might have heard the term. Despite what popular culture says, Game Theory is actually a rigorous mathematical framework for understanding conflict and cooperation, with deep links to complexity science.

Formulated in the 1940s by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, and later famously expanded by John Nash, it examines how "players" make decisions when their success is contingent on the choices of everyone else. Game Theory is essentially the science of strategic interdependence. This is critical to remember, because the pandemic response could be framed as exactly that: a game of strategic interdependence being played globally, nationally and locally - multiple players, multiple objectives, all on the same interconnected board.

The foundational "game" in this field is the Prisoner’s Dilemma, which illustrates one of its core (and tragic) paradoxes: two rational individuals might not cooperate, even when it is in their best interest to do so. To get a visceral feel for how these dynamics evolve and also how trust is built, broken, and restored, I highly recommend spending ten minutes (ideally more) with Nicky Case's brilliant interactive project, The Evolution of Trust. Aside from being one of the most beautiful examples of interactive learning on the web, it is by far the most accessible primer on how the "scaffolding" of cooperation is constructed. Playing the game will give you an immediate sense of what follows without any need for the complex underpinning math. So seriously, go there first; it will be well worth your time.

*If you’re reading this at work, you can put the time you spend playing this game under “professional development”! It will be fine, trust me.

This is just a screen capture from the game

Research on Game Theory and the Pandemic Response

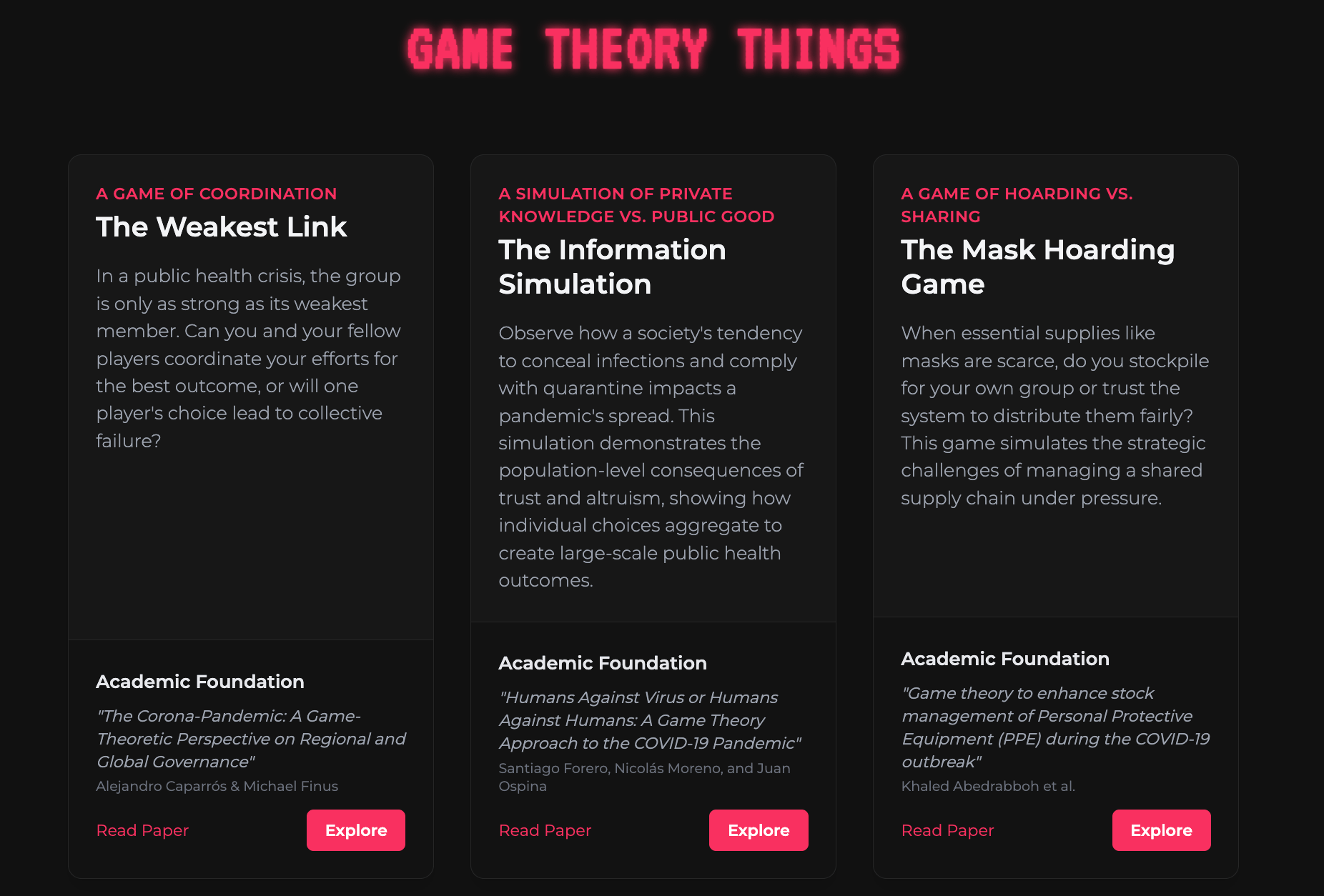

To take this approach one step further, and in the spirit of gamified learning, I’ve also translated a selection of interesting COVID 19 game theory research papers into an interactive experience for you to see how these concepts powerfully apply to more familiar questions.

This bespoke platform (created just for you!) offers a first-hand feel for the core ideas described in various papers and how these dynamics drive cooperation/conflict choices that countries, health systems and even individuals have to make in high risk situations. Links to the source research papers are also conveniently included within each simulation/game. Two of the games allow you to step into the shoes of a decision-maker, while the simulation shows you the impacts of how individual decisions (to report and quarantine versus conceal and go out) can have broader consequences:

The Weakest Link Game. Based on research by Caparrós & Finus (2020), this game explores how global outcomes are often determined not by the strongest players, but by the "weakest link" in the chain. It challenges you to coordinate resources in a system where one failure can derail everyone's success.

The Information Simulation. Drawing from Forero, Moreno, & Ospina (2021), this simulations explores the society level impacts of individual choices between transparency and concealment. You play the role of an observer in a scenario where you set community attitudes to concealment and compliance (of COVID positive status) and how individual level decisions influence with the overall burden to the community.

The Mask Hoarder Game. Based on Chen & Schmidt (2021), this game simulates a "Public Goods Game." You'll face the rational temptation to "defect" by hoarding PPE to protect your own team, even if it degrades the supply for the entire hospital.

“MacGyvering” our way out of the Pandemic

With this intuitive understanding of game theory under our belt, we can now better illuminate the patterns we saw in 2020. We can begin to frame them as ‘locally rational’ and tactically smart decisions to a growing awareness that the rules of the game had fundamentally shifted.

In my role with the Bridge Labs program, I was watching two distinct 'games' playing out. I was also very lucky to have access to the expertise of key thought leaders like Professors Sidney Dekker, Paul Salmon, and Evonne Miller, who brought their own unique perspectives to the real-time evolution of what we were seeing.

From a game theoretic perspective, we could see that high-level leadership were attempting to retain order and technical control through rapid-fire directives, broad and repeated assurances that everything was under control, and sometimes by running intrusive compliance and stock checks. Meanwhile on the frontline, clinical colleagues were playing a much grittier game of pure survival.

The first real stress test of this mismatched game was the global personal protective equipment (PPE) shortage. Much like our North American and British colleagues, we were hit hard with PPE supply concerns in Queensland. Globally, health leaders were understandably focused on inventory spreadsheets and expanding procurement pipelines. While that was happening, clinical teams were already doing the grim math of survival on the proverbial ‘back-of-the-napkin’. Their central concern was how eventual shortfalls might affect them, their patients, colleagues, and loved ones.

Photo by Jonathan J. Castellon on Unsplash

In Australia, we are very reliant on importation for most consumables, so the risk of complete border closures (which eventually did occur) could prove catastrophic. Understandably, clinicians were worried. One unique development we saw in the early stages of the pandemic was when some higher-risk clinical teams proactively initiated contact with local garment manufacturers to explore their capacity to mass-produce cloth masks - a move straight out of the MacGyver pilot episode. While no one was under any misconception that cloth-based masks were a perfect (or even adequate) solution for a .1 micron virus; in a world where the official 'scaffolding' was already beginning to creak, a cloth mask was better than having nothing at all.

The spirit of ‘Jugaad’ (a rich and layered term for frugal innovation from Hindi) didn't stop at masks.

When the "surge" eventually materialised, the pressures on ventilators quickly reached crisis levels across many intensive care units (ICUs) across the country. We began hearing of interstate teams exploring the modification of ventilators to serve two, or even four, patients simultaneously using 3D-printed Y-connectors. It was a technical "Hail Mary" that sent shockwaves through the more risk-averse layers of clinical governance (and is probably causing palpitations for some readers).

On one level, it was an unthinkable breach of safety standards, a dangerous deviation from prescribed practices, but to an experienced clinician standing at a bedside with five gasping patients and only two machines, it was a locally rational gamble between a desperate but highly creative attempt to save lives, and the certainty of a "lose-lose" outcome.

Protocols like the Columbia/New York Presbyterian Ventilator Splitting Protocol began to spread over backchannel peer-to-peer (P2P) networks like wildfire. Sometimes dismissed as reckless or 'cavalier' in some high-level circles, these often included deeply sophisticated, adaptive safety measures designed to manage the worst risks. But in many global systems built on rigid control, clinicians often chose to go dark. In many instances, healthcare ICUs that adopted such protocols would conceal these innovations from leadership until quite late because of a fear of being shut down.

The concealment often ran in both directions: behavioural economics studies during the pandemic highlighted how leadership teams frequently suppressed or downplayed information about critical upstream supply chain shortages or on anticipated delays in delivery of critical equipment. While these strategies were grounded in defensible logic, such as to avoid panic and stockpiling, they were ultimately ineffective as frontline teams (through their own global clinical networks) often had a good enough idea what lay ahead and did it anyway.

This ratcheting down of mutual trust and transparency became a major strategic disadvantage against the main player on the board: the rapidly mutating COVID-19 virus - which behaved a lot like the ever-evolving adversary from the upside down in Stranger Things - seemingly always two steps ahead, while the heroes of the series were frustratingly knee-capped by constantly having to evade shadowy three-letter agencies and a secret military program with an agenda all its own.

Several years on, and in the cool light of hindsight, it’s much clearer that many health systems, administrators and clinicians alike, became unsuspecting victims in a complex game of control and concealment. Administrators would mask shortages to project stability, and clinicians would mask their local 'MacGyver-isms' to avoid being shut down. To an extent, all of us failed to appreciate that the actual the rules of the game was changing much faster than anyone could keep up with.

As we saw, Game Theory offers some compelling insights into all of this, revealing that what seemed chaotic or short sighted was really a series of rational, tactical moves scaffolding on each other in a ever-changing game, and one in which trust was quickly eroding.

Why this Matters When Thinking about Current Challenges

The core insight I want to emphasise is that the pandemic didn’t create new behaviours because of the once-in-a-lifetime crisis but just surfaced and amplified the locally rational objectives (and patterns of behaviour) that already existed within most systems. The thought patterns that gave rise to peculiar public behaviours we witnessed during the pandemic (like the bizarre phenomenon of toilet paper stockpiling) haven’t gone away, they have just retreated back into everyday life when things returned to something close to normalcy.

In the context of healthcare however, this game is still being played out in some arenas - such as the escalating mismatch between demand and capacity in most western health systems.

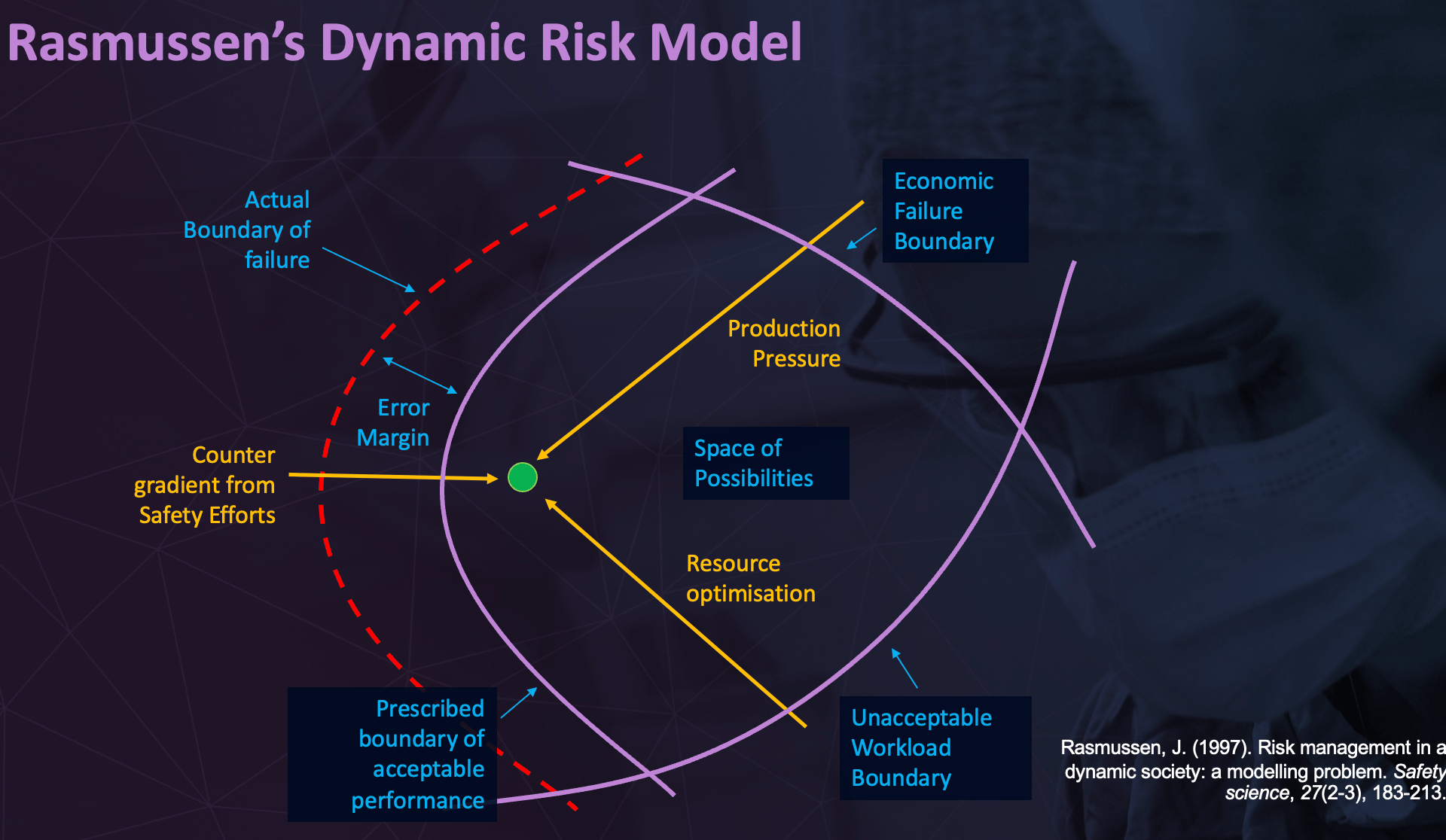

A critical mistake organisations often make is to treat things like hospital capacity, patient safety and staff wellbeing as separate problems to be managed via separate resource buckets and decoupled management structures. In reality, as Jens Rasmussen identified decades ago in his Dynamic Risk Management Model, these are in fact deeply interconnected issues within the same complex system.

Rasmussen, J. (1997). Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Safety science, 27(2-3), 183-213

Rasmussen described a system as operating within three boundaries: the boundary to economic failure (efficiency), the boundary to unacceptable workload (safety for staff), and the boundary to a major accident (safety for patients). The system's "operating point" is sensitive to all of them. When we manage issues through command-and-control measures such as to solve a capacity crunch, we are essentially pushing for higher efficiency and throughput and implicitly emphasising that over other considerations. Pushing the operating point harder toward the efficiency boundary inevitably drifts it closer to the boundaries of staff burnout and compromised patient safety.

But from a game theory perspective, we can see there is more to the picture. Over time, clinicians can come to see these organisational moves as a deliberate and systematic attempt to shift the burden of system deficiencies onto them. Seeing the chronic overwork, fatigue, burnout, and staff attrition it creates, the workforce might stop playing the "long game" (where we all build trust to work together) and instead shift into a series of one-off adaptive survival moves. In essence, frontline teams might shift strategies because they percieve a fundament change in the rules of the game.

In situations where organisational decisions are perceived as threats, the tactic to focus entirely on looking out for yourself and the ones around you becomes completely rational even if it ultimately counterproductive for everyone. In this context, concealing actual capacity or overestimating current workloads becomes a beneficial game-play strategy just to retain enough of a short-term buffer to deal with the many crises that will inevitably arise within the complexities of everyday patient care.

Unfortunately, few health systems tend to think about these complexities in game theoretic terms and often suffer as a result of it. Organisations can end up in quite fractured relationships with their workforce or with no residual resilience (adaptive capacity) to deal meaningfully with future surges. Even in these scenarios, Game Theory can offer insights on to reclaim that vital commodity for cooperation - trust.

Protecting “The Rules of the Game”

If we accept that counter-intuitive moves by various players are rational responses to a broken board, then the focus must shift from policing compliance (enforcing play on the broken board) to efforts that restore and preserve the "cooperative" nature of the game (by fixing the board). Once that is done, we might deploy additional strategies that arrest its future slide into conflict. Here are a couple of examples to get you thinking:

Participatory Design as a Trust Signal: Inviting genuine feedback from operational teams on the presenting challenge before a strategy is formulated is one of the most powerful trust signals a leadership team can send. Whether through informal means, open forums or collaborative technology, engaging those who will live with the consequences of a decision (frontline teams) reduces then need for adversarial game play and preserves cooperative partners in a shared goal.

Resisting the urge to constrain autonomy: We must be wary of any strategies that solve a central capacity problem by stripping away local autonomy or pulling resources away from doing and into policing. Examples of this include implementing new procedures (increased red tape) or instituting complex approval processes (such requiring increasingly higher levels of authorisation), reduced access to discretionary resources or directives that attempt to override clinical judgment. When clinicians feel they are losing the ability to manage their own pressures and environment, the risk of an "adversarial game" skyrockets.

Protecting professional autonomy is a powerful check against the emergence of survival-mode concealment (or non-transparency) strategies. No doubt, this is not easy in many situations where resource shortfalls means there will be a degree of pain to spread around. But even acknowledging the risk of negative temporary impacts on clinical autonomy, and showing genuine willingness to negotiate out of that situation at a future time, can go a long way to protect vital trust-based relationships in the long run.

Closing the loop and having cross-cutting conversations: Trust is better preserved when people feel heard after the fact. Creating a space where the on-the-ground impacts of a new strategy can be aired allows for the sharing of both anticipated and unanticipated consequences, sometimes far downstream. It is a way of saying: "We know that something we did changed the rules of the game for you. We want to know how that has affected your work, and what we need to do to make sure the game feels fair for everyone again."

Photo by Clint Bustrillos on Unsplash

Astute fans of Stranger Things will know that the series is held together by a much older game: Dungeons & Dragons (D&D). D&D serves as a key inspiration and critical narrative scaffold for the entire series. When the young protagonists faced something inexplicable and terrifying in series one, they often retreated to the basement to consult the D&D Player's Handbook: the rules of the game.

In many ways, referring to game theory is our version of that basement strategy session.

Much like the characters in Stranger Things, we (clinicians, administrators, or members of the wider community) too, do similar things when faced with something threatening or hard to understand: we instinctively reach for our internal playbook to see if rules of the game have indeed changed. In healthcare, these shifts (unlike in D&D) are rarely announced with a roll of the dice; instead they happen quietly, incubating in the interstitial spaces of everyday operations. Becoming sensitive to the ways in which such changes might induce unexpected behaviours can create a powerful protective buffer around those vital trust-based relationships that are non-negotiable for cooperative operations in complex systems.

A better handle on Game Theory can offer healthcare leaders the frameworks and tools required to steward finite resources wisely while remaining attentive to the adverse effects of well-intentioned measures on these indispensable but fragile and contingent links.

After all, the lights only start to flicker once the rules have already changed…

Happy New Year everyone.

Subscribe and never miss an issue, unlock additional resources at the end of each newsletter and get full access to previous content!

The Human Stream is a monthly newsletter for clinician improvers, safety and quality professionals, governance teams and healthcare leaders. The Human Stream compiles insights, topic overviews and practical tips from contemporary safety and systems sciences, all in an easy-to-read, information-rich package, conveniently delivered to your mailbox!

AI Use Declaration: AI was used to support research and to help build the gamified learning examples provided this post. All other material is written by a human. All quotes are verified and directly taken from source document.